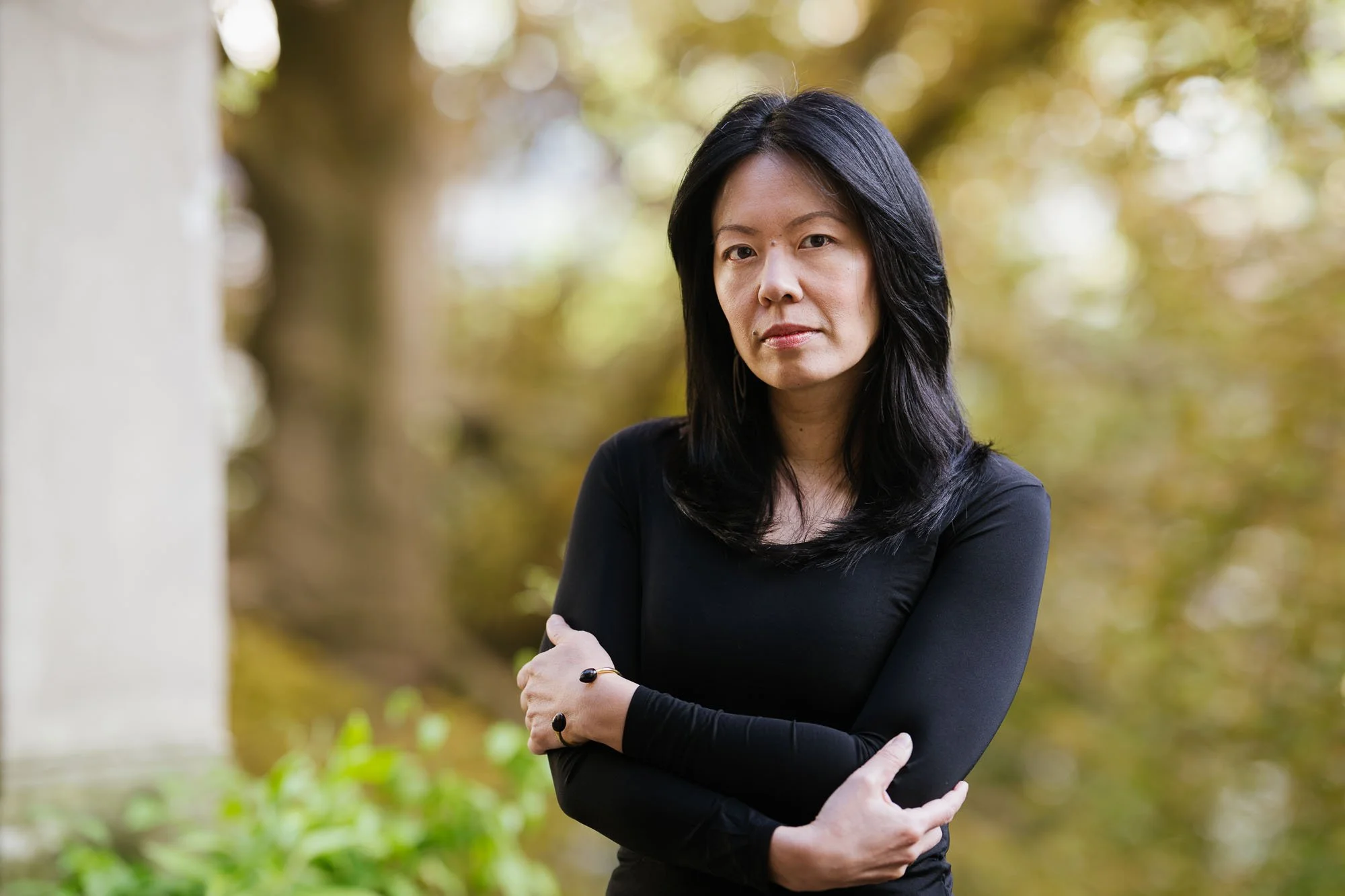

WRITER AND JOURNALIST

Photo: Alena Schmick

I was born in 1982 in Berlin, the oldest of three children in a Vietnamese family. Today I`m part of a new generation of German writers addressing questions of race and identity.

Brothers and Ghosts, my first novel, is loosely based on the journey of my family. Set in Berlin, Saigon and California, it tells the story of a young woman struggling to reconcile two cultures within her, and of her family which was torn apart by the Vietnam War. It took me four years to research and write the German original, so I`m excited it now gets to travel the world through its English translation by Charles Hawley and Daryl Lindsey. The book was also adapted to stage, KIM. For readings and performances, please check out my events.

For more than a decade, I`ve also been a staff writer at the weekly Die Zeit. In 2023, I was the first journalist to interview the actor Kevin Spacey ahead of his sexual assault trial. In 2020, I co-wrote an investigation on the Essex lorry deaths, which was nominated for the the German version of the Pulitzer Prize. In 2012, I published We new Germans with Alice Bota and Özlem Topçu: a non-fiction book about our own experiences and the second generation of immigrants in Germany.

I studied Media and Communications at Goldsmiths College and Sociology at the London School of Economics. My first work stints included freelance work for the Guardian and NPR´s Berlin Bureau.

Today in live in Berlin again – on the outskirts of town, in the green and sleepy area of my childhood. In addition to my writing work, I`m part of this year`s jury for the International Literature Award and a founding member of PEN Berlin.

You can contact me at hi@khuepham.de

Fiction

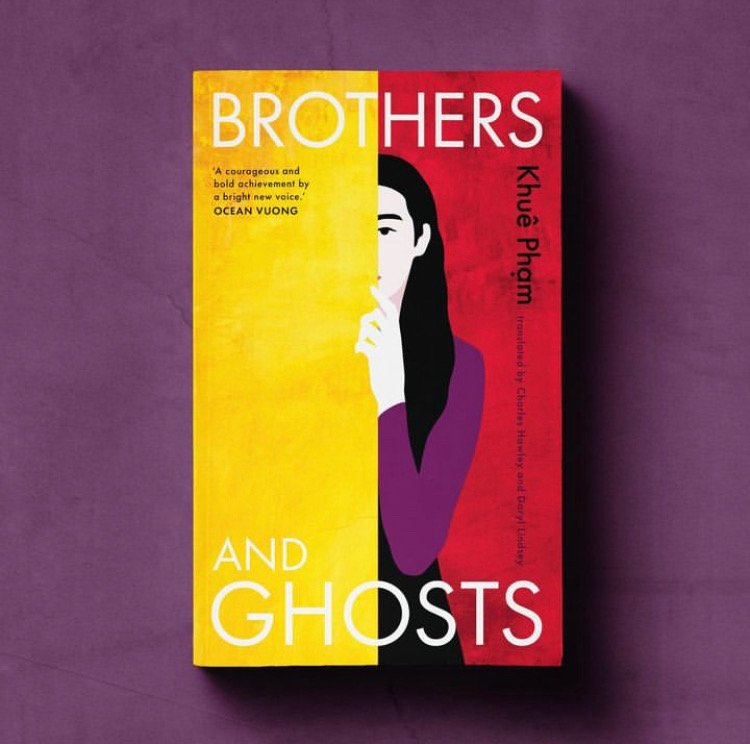

BROTHERS AND GHOSTS

translated by Charles Hawley and Daryl Lindsay

“Pham’s novel marks a seminal accomplishment that tells the dignified, thorough, and epic story of a Vietnamese family through clear, gem-like sentences and unflinching observations. With Pham’s vision, nothing is left unturned and all things are salvaged and lost at once. A courageous and bold achievement by a bright new voice.”

Ocean Vuong, “On Earth We`re Briefly Gourgeous”

"A novel about the paths we take, the secrets we hide, and the familial duty that binds us. Khuê Phạm coaxes out the stories that live in darkness and the light she shines is captivating. Gorgeously written, Brothers and Ghosts is a book that stays with you long after you close it."

Eric Nguyen, “Things We Lost to the Water”

“Illuminating and unforgettable, Brothers and Ghosts is a house that reveals secrets behind each door: a country torn apart by colonialism and civil war, a family divided between loyalty and freedom.”

Juhea Kim, “Beasts of a Little Land”

Kiều calls herself Kim because it’s easier for Europeans to pronounce. She knows little about her Vietnamese family’s history until she receives a Facebook message from her estranged uncle in America, telling her that her grandmother is dying. Her father and uncle haven’t spoken since the end of the Vietnam War. One brother supported the Vietcong, while the other sided with the Americans.

When Kiều and her parents travel to America to join the rest of the family in California to open her grandmother’s will, questions relating to their past—to what has been suppressed —resurface and demand to be addressed.

Reviews

“The novel, like a tightrope walker, is poignantly poised above the open abyss.”

NPR

“Brothers and Ghosts is an elegant exploration of what it means to grow up in a home that does not belong to you and to inherit the emotional and cultural vacuum created by the catastrophe and trauma of war.”

The Saturday Paper, Australia

“Brothers and Ghosts is part of a literary wave from the Vietnamese diaspora that shifts the focus away from the American experience of the war, and questions the simplistic way in which Vietnamese people are viewed. (…) The stories of Kiều, Minh, and Sơn provide a snapshot of the complexity of the Vietnamese diasporic experience, and how families can grow together as well as apart.”

Asian Review of Books

“Looking at the Vietnamese community in the US, I always felt a sense of envy”

A podcast with Kenneth Nguyen (“The Vietnamese”)

Why do you think we run away from our history and culture?

Khuê Phạm: Growing up in Germany, I felt a constant sense of distrust. People would always ask me, “where are you from?” And I would say, “I’m from Berlin,” because I was born in Berlin and I had a German passport and I speak German so much better than my crappy Vietnamese. Yet people wouldn’t believe me. They would always say “No, but where are you really from?” It made me quite angry and I think it made me quite angry at my Vietnamese heritage.

Eric Nguyen: In your book, Kiều asks, “how much does it take to understand where you come from?” How would you answer that question?

I wrote this book because I feel that you cannot really understand yourself if you don’t understand your family. When Kiều goes to California to spend time with her relatives, she moves outside of her comfort zone into a zone that is unfamiliar and scary to her. But the more she engages, the more she realizes that a lot of her own values are shaped by the values of her family. The dark experiences of being a refugee, of being in a country at war, they’re covered in silence, but somehow that silence is passed on from one generation to the next. We have it in us, we just don’t really know how to name it.

Do you see feminism as changing between different cultures and generations?

As an Asian woman, people have a lot of assumptions about me, and that often leads to people like me being underestimated. I think people like me have to be much tougher to raise their voice and make themselves heard. My female characters are testament to that. On one hand, you may underestimate them when you first see them, but when you look deeper, you realize how strong they are.

KIM

Stage adaptation of “Brothers and Ghosts” by Fang Yun Lo and Khuê Phạm. KIM was shown in theatres in Germany and Taiwan

Theatre

ARTICLES

Non-Fiction

WE NEW GERMANS

In 2012, I published the non-fiction book “Wir neuen Deutschen” with Alice Bota and Özlem Topçu. This excerpt was translated by Daryl Lindsey. You can read an interview here.

Can there be anything wrong with the question of where someone comes from? Those who ask the question can usually answer it. They are people whose parents and grandparents have grown up in this country, whose names sound familiar and sometimes appear dozens of times in the phone book. People who ask this question usually aren't satisfied with a simple answer. Instead, they keep asking more questions:

"Do you prefer to be in Turkey or here?"

"Are you more Vietnamese or more German?"

"Is there anything Polish about you anymore?"

Those who ask these questions want to gain a better understanding of us because our names and life stories sound odd and foreign to them. We choose our answers carefully, not wanting to offend anyone. We don't want to sound as if we prefer one country over another. We don't want to seem ungrateful or disloyal. And we don't even know the answers that well ourselves, which is why we sometimes say: "I'm both" or "I'm neither." It's essentially the same thing.

When we say these things, there's something else we're not saying. The real question hangs in the air unanswered: the question of home. That's because the question of home is such a difficult and painful thing, something so filled with longing that it's hard for us to talk about, much less answer.

For us, home is the emptiness that was created when our parents left Poland, Vietnam and Turkey and went to Germany. Their decision to do so created a gap in our family history. We grew up in a different country from our parents, speaking a different language and with different songs, images and stories, ones they didn't know. We couldn't learn German traditions from them, and even less so the sense of belonging to this country. We just know it secondhand: the sense of having a homeland that our German friends feel because they inherited their place in this country -- and their certainty.

There are many ways to interpret the German concept of Heimat, or home. In Polish, it's mala ojczyzna or "little fatherland"; in Turkish, it's anavatan, or "motherland"; and, in Vietnamese, it is que huong, or "village." Despite the differences among these concepts, they all refer to the link between biography and geography: Home is the origin of the body and soul, the center of one's own world. A country's culture shapes the character of the people who grow up there. It raises them the way fathers and mothers raise their children. It makes the Germans disciplined, the French charming and the Japanese polite -- at least that's the general perception. But what does this mean for those who grew up in two countries? Do they even have a home? Or do they have two? Why is it that, in German, the word 'home' cannot be plural?

Imagine a girl who learned how to read and write in Poland and came to Germany when she was eight. It was only here that she learned the language that she turned into her profession. Is she really Polish? Or a child that lived in Turkey for three years, and then grew up in Flensburg, in northern Germany, in a world that was half Turkish and half German. What's her home? And a German who looks Vietnamese, who lives Germany and has only visited Vietnam during summer holidays? Does she even have a native country?

The fractured histories of our families make it difficult to clearly say where we come from. We look like our parents, but we're different. We're also different from the people we work or went to school with. In our case, the link between biography and geography is broken. We aren't what we look like. We don't know what percentage of us is Polish and what percentage is German because we don't think in those terms. We have often asked ourselves whether our sense of humor, our sense of family, our pride and our emotionality comes from one country or the other. Did we learn these things from our parents? Or in our German schools? Or by watching our friends?

We wrote about the dichotomy in our diaries, asking ourselves: Who am I, if I don't know where I come from?

We lack something that our German friends, acquaintances and coworkers have: a place that they don't just come from, but where they belong, where they can find answers to their own questions and encounter others who are like them -- or at least that's what we imagine. We, on the other hand, come from nowhere and belong nowhere. There is no place where we can overcome our dichotomy because it lies in the no-man's-land between German and foreign culture. When we're together with our German acquaintances and colleagues, we often ask ourselves: Do I really belong? And yet, when we're sitting with our Polish, Turkish and Vietnamese acquaintances and relatives, we ask ourselves the same thing.

We yearn for a place where we can simply be, without having to simulate it. But we also know that this isn't a place, but rather a state of mind.

Our attitude toward life is characterized by alienation, accompanied by the fear of disturbing others in the harmony of their sameness. We are afraid that others will perceive us as foreign objects. It isn't a feeling we talk about very much. After all, who would understand us? We want to be normal. And, if that's not possible, at least we want to pretend as if we were.